Part 3 of 4

Jalan Pandanaran is a busy four-lane street in downtown Semarang, a city of 1.6 million people that is also the capital of Indonesia’s Central Java province. Its prime location connecting the city’s main square with a major roundabout to the west has attracted all sorts of businesses, from banks and media companies to government offices, hotels, restaurants and traditional snacks shops. If you drive its length, however, a bronze animal statue at its south side will likely steal your attention.

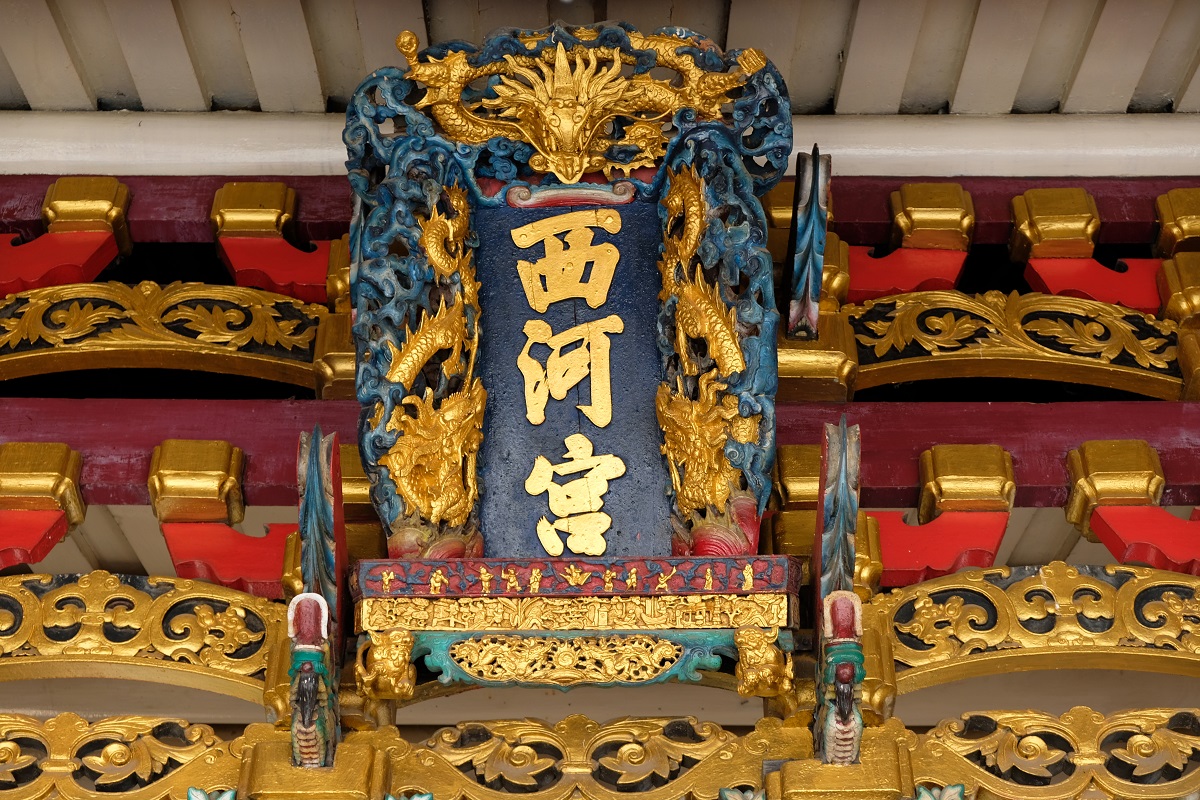

At a first glance, you might wonder what kind of creature that is. Is it a dragon? or a camel? or maybe a goat? In fact, it’s actually a combination of the three, a mythical beast called Warak Ngendhog that is believed to have originated in Semarang. In 1881, the local regent initiated a tradition to mark the beginning of the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. He would go to the city’s main mosque to hit the bedug (a large double-headed drum usually found in traditional mosques in Indonesia) which created the sound “dug”, then followed by the lighting of gunpowder nearby with a “der”, or bang. And Dugderan was born, an annual tradition still carried out in the city to this day. Apart from the cacophony, a night market has also been held since the inception of this festival, where vendors have always sold miniature Warak Ngendhog.

No one knows for sure who invented the creature, but everyone agrees that it’s a product of acculturation among Semarang’s ethnically diverse populace. Although variations exist – some say the head is of a Chinese dragon, the body of an Arabian camel, and the feet of a Javanese goat – one thing is always certain: Warak Ngendhog is influenced by the city’s Javanese, Chinese and Middle Eastern/South Asian cultures. This shouldn’t come as a surprise since Semarang has always been one of the most important ports on Java, even long before the Dutch arrived and began colonizing the island. The city attracted Muslim merchants from across the Indian Ocean who not only traded with but also introduced Islam to the locals, as well as Chinese workers and businessmen – among them were the father of Singapore’s first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew.

However, if we talk about the history of Semarang’s Chinatown, we should also look at what happened in Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in the 18th century where a harrowing event unfolded and left a long-lasting impact on Chinese communities across Java.

When the Dutch began their domination on trade routes in the East Indies, they hired many Chinese immigrants to work on construction projects in Batavia – the center of Dutch trading activities in the region – as well as on sugar plantations on Java, among other things. In a relatively short period of time, the port city’s Chinese community grew to a considerable number, and many of them became visibly wealthy. At this point, strict regulations imposed by the Dutch on the ethnic Chinese were already in place with the threat of deportation for those who didn’t comply. However, a malaria outbreak in 1730s further tightened these rules, partially fueled by an increasing suspicion and distrust from the Dutch toward the community. Resentment also grew among the indigenous population partially due to the conspicuously widening wealth gap between local people and immigrants, despite the fact that there were also a lot of poor people in Batavia’s Chinese community.

Rumors spread among the minority group that some people from their community deported by the Dutch were thrown overboard in the middle of the sea, and some died in riots that broke out on ships. Exacerbated by the falling price of sugar in the world market, which badly hit the sugar industry in the Dutch East Indies, discontentment began to boil among poor ethnic Chinese people who felt the brunt of the economic downturn. Adriaan Valckenier, the governor of the VOC (Dutch East Indies Company) at that time, then gave orders to respond to any uprisings from the Chinese community with deadly force. On October 9, 1740 all hell broke loose. Ethnic Chinese were targeted by the VOC soldiers and some locals in a widespread massacre that only ended one and a half months later. It is estimated that in the aftermath of the pogrom, more than 10,000 ethnic Chinese lost their lives, and many who survived decided to flee to the east including to Semarang. In Batavia itself, new regulations were imposed by the Dutch which required all ethnic Chinese population of the city to resettle in a designated area just outside the now-demolished city walls to make it easier for the Dutch to control them. And that was how Jakarta’s Chinatown was born.

On top of what happened in Batavia, Semarang’s Chinatown was conceived from another event closer to the heart of the Sultanate of Mataram, a Javanese-Islamic monarchy which dominated much of what is now Central Java, Yogyakarta and part of East Java provinces from the 16th to the 18th centuries. Internal strife among princes of Mataram as well as separatism in some of its territories brought in the Dutch who saw these crises as a chance to divide the sultanate and conquer it. Amangkurat V, Mataram’s ruler who was waging a campaign against the Dutch and other princes who were allied to the European power, received support from the ethnic Chinese community whose memories of the Batavia massacre in 1740 then followed by another one in Semarang a year later (also in other cities in the subsequent years) were still fresh. However, the VOC ended up on the victorious side, and the same regulations applied to the ethnic Chinese community in Batavia were also imposed in Semarang, a port city that once belonged to Mataram but was then ceded to the Dutch as part of Amangkurat II’s debt payment more than six decades earlier.

In spite of some limitations the ethnic Chinese had to live with from that moment on, they were (and still are) known as resilient people who will thrive even under the most challenging circumstances. Within the confines of the designated Chinatown (Pecinan in Indonesian) area directly south of the long-gone walls of the Dutch commercial district (present-day Kota Lama), businesses flourished. And in the centuries that followed, Semarang’s ethnic Chinese community grew into prominence and contributed a lot to the city, from enriching its cultural identity to introducing new ingredients and dishes that have now become an integral part of its culinary scene.

Apart from being the birthplace of Lee Chin Koon (Lee Kuan Yew’s father), Semarang was also where Oei Tiong Ham was born. Many of us may not know his name today, but in the early 20th century, he was considered the richest man in Southeast Asia, with a business empire comprising sugar plantations, a bank, a steamship operator and a trading company, among other ventures. His conglomerate even had overseas offices in Amsterdam, London and New York. But even for regular Chinatown residents, life was good and things in general worked quite well, until the rise of Suharto – Indonesia’s second president – in 1966 who would lead a US-backed authoritarian regime to rule the country for 32 years. Among his most controversial policies was the prohibition of anything Chinese, from celebrating the Chinese New Year to having Chinese names, as a part of a nationwide Communist purge following a failed coup by the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) – he created narratives to equate the ethnic Chinese in Indonesia with the citizens of the People’s Republic of China.

Since then, many members of the minority group kept a low profile, trying to live their lives without attracting too much unwanted attention upon themselves. In 1980, however, Semarang’s ethnic Chinese residents faced another dark chapter of the community’s history in the city. What started as a minor skirmish involving a few Javanese and ethnic Chinese people in the city of Solo escalated into racial riots in other cities in Central Java with the worst of it happening in Semarang, the provincial capital. For several days in November that year, houses and businesses owned by Chinese-Indonesians were targeted by rioters who destroyed, looted and burned those properties. When calm was finally restored, the damage had been done and the wounds had been inflicted, both in physical and mental terms.

Residents of Semarang’s Chinatown began to grow increasingly confined to their houses. What was once a lively neighborhood turned into an area filled with people who sought refuge in their own dwellings, their own fortresses of solitude. Interactions diminished greatly as suspicion became a tool of survival. And to some extent this was the norm until 2000 when Abdurrahman Wahid – Indonesia’s fourth president who led a country severely crippled by the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis that also put an end to Suharto’s rule – revoked the prohibitions directed at the ethnic Chinese minority that had been imposed for more than three decades. In the wake of this, a number of people began implementing gradual efforts to bring the city’s Chinatown back to its former glory. James and I spoke to an architect who initiated this project. She told us how in the beginning it was very hard to talk to the locals about revitalizing Chinatown, and how she had to go door to door to talk to some of the residents and convince them to take part in it. Slowly she started gaining their trust, and a few years later a night market known as Pasar Semawis was inaugurated where residents of Chinatown as well as those from within and outside Semarang can try some Chinese or Chinese fusion (Peranakan) dishes and snacks that might otherwise be quite difficult to find outside this area. I remember around ten or eleven years ago some of my coworkers in Jakarta asked me about it and said how curious they were to go and see the market for themselves.

Rumah Kopi, a mid-19th century Neo-Classical landhuis (Dutch colonial country house) in Semarang’s Chinatown

Today, Semarang’s Chinatown is an area with narrow streets, numerous active Chinese temples and restaurants with Chinese names selling Chinese and Chinese fusion food. I don’t know how much of this was only made possible once the restrictions were lifted in 2000, but life here seems pretty much normal to my visitor’s eyes. Meanwhile, Kota Lama is still undergoing a major transformation that has made it a more appealing place to hang out with one’s family and friends. Nestled between the two, however, is an area that is often overlooked despite its equally interesting history. Known as Pekojan, this was the center of the city’s South Asian Muslim community who came to Semarang mainly to trade. Named after an area called Koja/Khoja in present-day Gujarat, India, it also grew into an important economic center of Semarang which complemented Chinatown and the Dutch quarter. Unfortunately, most of the original houses of the South Asian residents have long gone as many of them were sold to cater to the expanding Chinatown. Among the few remnants of the original Pekojan is a mosque that was built by the Muslim traders in 1878. Despite the multiple expansions it has undergone in the past, one tradition remains unchanged from the time of the original Gujarati settlers: serving a dish called bubur India (Indian porridge) during Ramadan. I have yet to try this, but from what I read this dish is made with a combination of South and Southeast Asian ingredients, including cinnamon, galangal and lemongrass.

A bit further from Chinatown and to the west of Kota Lama is a neighborhood called Kampung Melayu, literally Malay village. Its location right at the western bank of the Semarang River and close to the city’s old port made this area favorable not only to Malay traders, but also those coming from Pakistan, India and even Yemen to settle here. A lighthouse* was built here to guide incoming ships to Semarang. But when the Dutch colonial administration moved the port further west and constructed another lighthouse in the new location, the old tower was then turned into a minaret of a mosque that was built nearby to cater to the area’s large Muslim population. Upon its completion, the early 19th-century mosque had two floors. But due to land subsidence and saltwater intrusion that became more and more severe each passing year, its lower floor was rendered unusable and was eventually filled with earth in 2000. Only the upper parts of its windows are still visible today, and by the 1990s many of Kampung Melayu’s residents had moved somewhere else.

However, last year the mayor of Semarang published a video rendering of a revitalized Kampung Melayu with new riverside promenades, lots of trees, and some parks to complement Kota Lama’s rejuvenation. If you see how the former Malay village looks today and compare it to how the mayor envisions it to be in the future, it takes a little more than just imagination to picture how this seemingly difficult project is going to be carried out. I’d be pleasantly surprised if the result elevates Kampung Melayu’s character instead of taking it away, and I do hope the government learns from some of the mistakes they made when restoring Kota Lama. It would hugely benefit the city if Kota Lama, Chinatown, Pekojan and Kampung Melayu are all sensibly restored and revitalized so the residents can not only be proud of their heritage, but also of the interconnectedness among the city’s different communities. By then the people of Semarang can attest to Warak Ngendhog’s truest meaning as a representation of the city itself.

*Or more precisely a watchtower for the harbormaster

What a fascinating read Bama! How easy it is to tear the rich cultural tapestry of a land woven over centuries and how much harder to repair it. And the less said about the bogey of the ‘other’ fed to the majority, the better. We are all – Myanmar, us – still living it. I do hope they manage a sensitive restoration. The fact that they are attempting it is a step in the right direction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If only most people knew how much we would lose if we let such things happen. Yet, over and over again we’re seeing the same patterns keep repeating themselves as if we have never really learned. As for the restoration, currently I feel that the city government focuses more on beautification (to bring in more tourists) than heritage preservation. However, the plethora of scholars, architects and history enthusiasts in Semarang ensures that any deviations from conservation principles will be met with harsh criticism.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post Bama, this looks like a colourful and interesting place to explore

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Phil and Michaela. And the good thing is most of these places are within walking distance from the city’s Dutch colonial quarter which has become a trendy place in recent years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for another well written entry. I appreciate the history lessons here about the brutal oppression of Chinese. It’s just so sad to read and a reminder that racism has long, ancient roots. It was great to read about the restoration of Chinatown and I’m glad you had a chance to interview a key figure.

The buildings are just crying out for restoration / renovation. I just hope they’ll do it right.

You probably spend a lot of time researching, writing and editing your posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems like racism knows no boundary — although the reason in each country/region might be different, but the effect is the same. Ironically, having become a victim of racism doesn’t necessarily mean that a person will not say racist things to others from different communities. (I have witnessed this firsthand).

I talked to some people in Semarang about the conservation effort of these neighborhoods, and many of them mentioned George Town in Penang and Malacca — both in Malaysia — as prime examples of how to do heritage preservation right. But whether or not the same direction is what the city government has in mind for Semarang’s Chinatown, Pekojan and Kampung Melayu remains to be seen.

I actually did 😀 It always takes me a while to prepare a post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is once again one of your incredibly well-researched and beautifully written pieces, Bama. What a fascinating and harrowing history. I love how you juxtapose the amazing cultural traditions/symbols that can flow from the peaceful interaction of diverse cultures with the sorrow and violence when people get suspicious of one another and act out of fear. Racism never leads to any good outcomes, and like you note in a previous comment, so often the people who suffered from it in turn will respond in a racist way to others. It is so not what one would expect, and it always saddens me as we don’t seem to become wiser as a human race. Thank you for all the research you put into your posts – they are a delight to read and I always learn something new.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a home to so many different cultures, races and traditions, Indonesia has its fair share of racially-motivated violence throughout its history. Some things have got better, and some haven’t. Many Indonesians tend to get by and try to forget about the past, but I believe unfortunate circumstances like what happened in Semarang need to be addressed, not erased from our collective memory. In general, the state of race relations in the city is relatively good right now, but it could be a lot better.

Always appreciate your kind words, Jolandi.

LikeLike

I guess race relations can always be better anywhere in the world, Bama. Also it seems that no country has yet stumbled upon the correct formula for dealing with old wounds or improving current relationships. I always think diversity makes life much more interesting, which I guess is why people like you and I love travelling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said, Jolandi.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A riveting, thoughtful post, Bama. I loved the deep-dive into history and appreciated the fact that you didn’t gloss over the more confronting events including the Dutch-backed mass murder of 1740. I’ve met people in Hong Kong who have the impression that Indonesians hate the Chinese in general, because they remember the race riots in Jakarta and other cities that accompanied Suharto’s downfall in 1998. Although violence didn’t break out in Semarang at that time, I recall reading about how the ethnic Chinese community felt on edge and stashed improvised weapons in their homes in case all hell broke loose.

It is heartening to know that Chinese Indonesians can once again celebrate their culture after decades of forced assimilation. One of the community figures we met said it just isn’t possible to restore Semarang’s Chinatown to the way it was in the 1970s, when the old streetscapes and rows of traditional houses were still intact. I hope enough people step up to save what’s left, and wish the same for Kampung Melayu. That neighborhood really needs a helping hand – it was saddening to see the state of neglect combined with the effects of land subsidence. The ground floor of so many old houses there looked squashed, and I hadn’t realized the mosque was built with two stories until you told me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, James. After visiting Melbourne Museum, I now believe that addressing our past wounds is the right thing to do if we want to begin the long process of healing as a nation. We shouldn’t normalize glossing over terrible events in the past. Instead, we should look back at them and see how much we have progressed today. The oversimplification of “Indonesians hate the Chinese” certainly won’t help anyone, because as you might have realized by now after living in the country for almost five years, there are nuances to why things happened the way they did. Understanding this is key to preventing us from falling to the same hole again in the future.

I’m cautiously hopeful of the city government’s plan to revitalize these neighborhoods that surround Kota Lama, especially after seeing what they have done to the latter. However, due to the sorry state of many of those buildings, I think they need to move fast albeit careful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely thought it was a dragon-dog when I first saw your photo of the Warak Ngendhog. I so appreciate this deep-dive into the Chinese community of Semarang. I’ve long admired Indonesia’s fusion of cultures, but your post was both a reminder of colonialism’s unending painful impact upon the world and that as humans we continue to desire power and hierarchy over one another in absurd ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can see why the statue conjured up that image in your mind. 🙂 Indonesia’s fusion of cultures surely is special, but having honest discussions about circumstances when this was not the case is important. Unity in diversity is after all something that shouldn’t be taken for granted. It should be cherished and nurtured.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another insightful and interesting post Bama. I enjoyed how you wove in the Warak Ngendhog creature to emphasize the complexities, tragedies and richness of different cultures/people coexisting in the same place. I did not know that the Chinese minority were subjected to such brutality. The intent of symbols like the Warak Ngendhog is usually so noble but it is sad what often happens in real life. I think about my own environment with wonderful public art displays dedicated to our Indigenous Peoples and plaques about harmony and unity, when in fact racism runs rife. I’m also dismayed by Canada’s surge in anti-Chinese (and Asian in general) hate-crimes during the pandemic. But I digress. On a lighter note, I think I’ve mentioned to you before how delighted I’ve been in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries to see such bold and often over-the-top statues and monuments at roundabouts and other prominent locations. They’re fun to look at and it’s interesting to learn the stories behind them. Btw, I think it also looks a little like a lion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Caroline. Some cities in Indonesia have their own mythical beasts that are proudly displayed at busy intersections and roundabouts as distinguishing monuments. However, not everyone is aware of the philosophical symbols these creatures are supposed to tell people. It’s good that the city government of Semarang put up images and different interpretations of Warak Ngendhog with the hope that its residents will unite despite their differences. But I also think it’s equally important to talk about what happened in the past as a part of the long journey to heal the wounds.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed poring over the architectural differences in these ethnic quarters. What a huge difference between the more ornate Chinese buildings and the Dutch Colonial ones! Your country is one of great cultural breadth, and I hope the physical manifestations of that can be saved or restored. Oh, and the creature is a wonderful amalgamation of those cultures, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wouldn’t it be even more fascinating if a lot of buildings from that era had survived? I’m sure there are people who wish to buy those dilapidated houses and shops and turn them into something exciting without stripping them of their historical value. The thing is, purchasing any property in this part of the city can often lead to complicated paperwork and legal issues, which only add to the problem. But anyway, I do hope you’ll get to visit this part of the world one day in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me, too, Bama! And we have that same problem with disincentives to restore and rehab, even though our history is much shorter here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a shame that some places across the globe make it harder for people to take part in heritage building conservation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a colorful-looking place. Love this post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, John and Susan. Semarang is indeed known for its multicultural community which also explains the different colors you see here.

LikeLike

Semarang has an interesting past. History repeats itself certainly applies to the lives of the Chinese as this has happened to many communities in other parts of the world where jealousy over other’s prosperity or religious intolerance cause riots.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sometimes I do wonder if we ever learn from our past mistakes. In many cases here in Southeast Asia, the prosperity of many members of the Chinese community is an indirect result of the restrictions imposed on them. They have to survive with those limitations which in turn make them great businessmen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was an amazing read Bama. So much history packed into one small area. I’m so glad the Chinese finally get to enjoy a normal life now. What a lot they’ve been put through.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s hard to imagine that not too long ago, Chinese Indonesian communities across the sprawling archipelago had to endure such hardship — one that required them to erase their cultural identity. It was sobering to talk to some locals in Semarang about the changes in the city’s Chinatown. Fortunately, things are much better for them now, although there is still much room for improvement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hear no evil, speak no evil …. wait, why do no evil sih?

Kenapa bukan?

Ah sudahlah hahahaha.

Dan aku baru tau kalau Pekojan itu ternyata lebih berhubungan dengan muslim Asia Selatan, karena di Kudus juga ada area yang namanya Pekojan, tapi justru lebih didominasi oleh keturuan Tionghoa. Jadi selama ini aku pikir Pekojan itu nama lainnya Pecinan. Makasih udah meluruskan pemahamanku soal ini Bam.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nah, bingung kan mau mendeskripsikan apa untuk yang satu itu?

Mungkin Pekojan di Kudus ini agak-agak mirip sama Pekojan di Semarang yang sudah banyak ditinggal oleh Muslim keturunan India yang memilih untuk pindah ke tempat lain (kalau kasus Semarang mungkin ke lokasi yang lebih tinggi kali ya).

LikeLike

The Warak Ngendhog is not only fascinating to look at but fascinating in the explanation of history and culture. I had no idea about the Chinese Indonesian population beign so harmed.

Your post is filled with glorious photos, colour and as always one of the most well researched blogs I know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad that Semarang has Warak Ngendhog which can help remind people of the importance of unity despite all the differences. In the past, the Chinese Indonesian community tried to stay low so that they wouldn’t attract too much attention onto themselves. But today they’re a lot more visible — from TV personalities to social media celebrities — which is definitely a huge improvement. Thanks for your kind and encouraging words, Sue!

LikeLike

A lighthouse in the middle of a town 🙂 You don’t see that every day. The traditional houses and pagodas remind me a lot of Hoi An and my city’s Chinatown. The structure is nearly identical, except for the roof.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That lighthouse really is special, not only because of its location, but also its history. I think I was told once that roofs play an important role in Chinese architecture — you can tell from which part of China a community was from just by looking at the roofs of the temple.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting! I think there are some distingushed features in the decorative patterns too. But I can’t tell what is what. At first, I thought the people in Semarang built such high roofs because of heavy rainfall. The steeper the slope, the easier the water can get off 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

There must be differences in the ornaments as well, although I can’t tell you what they are — I’m more familiar with South and Southeast Asian Hindu/Buddhist decorative elements.

LikeLike

In my understanding it was not a lighthouse but a harbourmaster look outpost, to keep an eye on the boats entering and leaving the harbour.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for this new information, Pak Yono. I have added this in the post as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds reasonable! Thanks for the info 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Another well written and well researched post of mas Bama!

If there is one thing I regret during my two visits in Semarang, it is that I didn’t explore the Chinatown really well. I didn’t go to Pasar Semawis either. Semarang is truly a Penang of Java waiting to be revealed! Its potentials are unseen, undeveloped, unpromoted. Similar to Bandung’s Chinatown and Kampong Arab around Jalan Alkateri and Pasar Baru.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Nug. It’s interesting that you mentioned about Bandung’s Chinatown. When I was still living there, I rarely explored this part of the city, except for a few times when I had to buy stuff for my classes. Well, to be fair back then I wasn’t as interested in heritage conservation as I am today. I hope you’ll get to visit Semarang again so you can visit its Chinatown and sample some of the dishes there.

LikeLike

The warak was originally just a toy sold at the Dugderan. Seeing that many children came to the night market, some merchants at the Pasar Pedamaran near the square saw a business opportunity. They made wheeled animal toys from what ever materials were available. Until the 1970s toys like that were widely sold at the annual Dugderan. They came in different sizes, from small to large. Some had hard boiled eggs attached. This is called warak ngendhog (endhog meaning egg in Javanese). The warak ngendhog was more expensive than the warak minus egg. When I was a boy a friend of mine from a well to do family would come home from the Dugder market with a large warak ngendhog. He would proudly flaunt his warak, pulling it back and forth on the street in front of his house, to the envy of the other children in the neighbourhood. In those days eggs were considered a luxury food and was only served on special occasions. Initially, the warak was seen as just a toy sold at the Dugder market. Later, however, the warak was adopted as the icon of Semarang and interpreted as a symbol representing the three main ethnic groups in Semarang.

LikeLiked by 1 person

‘Who got the biggest warak’ was the competition among kids back then. Maybe its present-day equivalent is ‘who got the latest iPhone’. Oh well. Thank you for sharing your experience, Pak Yono. I actually miss the time when toys were far simpler and more fun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mas Bama, tulisan anda tentang Semarang ini bagus sekali. 👍🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terima kasih banyak, Pak Yono. Senang sekali atas apresiasinya. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Not A Newsletter: Aug20 Edition - Kulture Kween

Pingback: Not A Newsletter: Aug20 Edition - Kulture Kween